As a creative writing teacher, I sometimes struggle to get concepts across to my students. That’s why I created the Amazing Story Spiral, a visual tool to help students plot stories from character rather than event. (You can read about the Amazing Story Spiral in a previous blog post here: http://writinginthedarktw.blogspot.com/2014/10/the-amazing-story-spiral.html)

Since then I’ve developed three more visual tools for fiction writers (I created all three when I was supposed to be reading student stories – avoidance is sometimes a writer’s best friend!). I’ve drawn pictures of these three tools and while I’m no artist (as you’re about to see), hopefully they’re good enough to get the idea across,

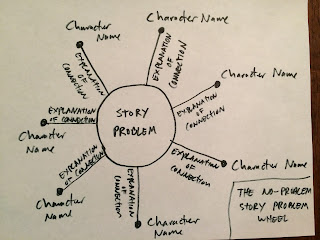

THE NO-PROBLEM STORY PROBLEM WHEEL

One of the most common problems my creative writing students have is difficulty keeping their stories focused on a specific story problem – a central conflict around which the entire action of the story revolves. A huge part of this difficulty is being unclear on how their characters are connected to the story problem. I created the Story Problem Wheel to help writers make sure that all their characters are connected to the story problem in ways big or small, and therefore serve a specific, vital function in the story.

This technique is simple enough. You write the name of each character on one of the spokes, and then you write an explanation of how that character is connected to the story problem. This technique can also be used as a plotting aid, for once you know how the characters are connected to the story problem, you can design scenes to show their connections.

For example, let’s say the main story problem is that Sally and Bob are separated, and Sally wants to get back together. One of the characters is Sally’s friend Joan. Joan’s connection to the problem is two-fold: she wants to support her friend, but she’s secretly in love with Bob, although she’s never expressed her feelings to him. Now we know that Joan’s role in the story: she will serve as an advisor to Sally while at the same time trying to convince her to divorce Bob for her own benefit. We’ve strongly connected Joan to the story, her role is integral, and we know what role she’ll play in the plot.

THE INCREDIBLE VIVID FICTION CHART

The more vivid fiction is, the more effective it is. Most writers, raised on a steady diet of movies and TV shows, usually only evoke the senses of sight and sound. But we experience reality on so many more levels, and writers need to be able to create the illusion of reality in their fiction by reflecting this richness of experience in their work. I created the Astounding Vivid Fiction Chart to give writers a framework to help make their fiction more vivid. Elements of experience are listed down the left side of the chart: dialogue, thoughts, emotions, sight, smell, taste, touch, hearing, memory connections, and imaginative connections. These last two might need some explanation. Memory connections are associations characters make when something in the present reminds them of something from their past. Imaginative connections are associations a character makes with his or her imaginative, like seeing a spindly, leafless tree in a graveyard and thinking it looks like a skeletal hand emerging from the ground.

The vertical sections of the chart represent units of a story – a scene, a paragraph, even a sentence, whichever you choose. As you’re working on a story unit, you can chart the experience details you use by putting a dot, an X, or a checkmark in the appropriate box. You don’t need to use all the different types of details every time. The chart can help remind you to make your fiction more vivid as you write it, but you can also use it to go over parts of a story you’ve already finished and chart how vivid those parts are. If you see you aren’t using enough variety of details or that you’ve fallen into a rut in terms of the details you use and you need to change things up, the chart can give you guidance for revision.

THE ASTOUNDING SCENE DIAMOND

Another difficulty students often have is considering the emotional aspects of their scenes as well as the action aspects of their scenes. In fact, they often neglect the emotional aspect altogether. This visual is designed to help writers think of the action level of their story along with the emotional aspect, with the story goal/throughline running through the middle of the chart. Action obstacles are on one side of the throughline, emotional obstacles on the other side. Each scene has both a physical and an emotional obstacle, and each scene has a reaction to the character’s dealing with those obstacles. The action and emotional qualities can be different aspects of the same obstacle. For example, a character wants to confront a rival at work. The confrontation is action. The anger the character feels during the conformation is emotional. The confrontation turns violent, and the rival punches the character. The character decides not to continue the fight and leaves. That’s action. The character also feels anger, shame, and self-loathing for retreating. In each scene, the character deals with both the action and emotional obstacles, reacts to them, then moves on to the next scene. The end of the story the climax has both an action aspect as well as an emotional aspect. The value of this chart is that it continually reminds writers to tend to the emotional level of their stories, making their fiction far richer in the process.

Give these three tools a try and see what they can do for you – and if you’re a teacher, feel free to steal them for your classes, and see what they can do for your students. Let me know how they work for you, and especially let me know if you find ways to improve them. After all, we’re all in this together, right?

Friday, November 27, 2015

Saturday, November 7, 2015

To Market, To Market

When you’re a writer, marketing your books is a

necessary evil. (And I’m a horror writer, so I know evil!) There are hundreds,

maybe thousands, of people out there who are only too happy to share their

advice on marketing fiction. Some of these people are relative newcomers who

are still trying to figure out the whole marketing thing themselves, while

others are seasoned professionals with years of experience who offer

tried-and-true techniques. But regardless of where all these people are coming

from, their advice has one thing in common: it deals with marketing a book after it’s finished. I’d like to suggest

that the most important marketing happens before

a book is written.

First, let me tell you a story. Several years ago I

was on a panel at a science fiction convention. The panel dealt with the

business of writing and the panelists were a mix of experienced and

up-and-coming writers. The moderator began by saying that if you’re going to

write, you must treat it like a business, and the other panelists echoed this

sentiment in turn. But when it was my time to add my two cents, I said that

writing is a creative act, and therefore has an artistic purpose at its core.

If writers’ sole purpose was to make money, we’d become doctors or lawyers. I

said it’s up to writers to decide what their goals for their writing are, and

they can write for pleasure, as a hobby, as a second vocation, or as their

primary vocation, but whatever they do, writing is ultimately a creative act,

not simply a business proposition. The other panelists then back-tracked a bit

and agreed that yes, the artistic aspect was the foundation of a writing

career, and the panel went on from there.

My point wasn’t to try to shut down the other panelists.

I wanted people to realize something essential about writing: only an idiot

goes into the arts with the sole purpose

of making money. You’re trying to sell a product – a book, a painting, a song,

a performance – that most people aren’t interested in. People who love the arts

forget that the arts have a very small audience when compared to the total

population. We’re selling a product with limited appeal, trying to sell it to a

small customer base, and we’re competing with all the other artists who are

trying to sell similar products to the same customers. From a business

perspective, this is a recipe for disaster.

The first thing writers need to realize when it comes

to marketing is this:

1. We’re

creating a product with limited appeal, we’re creating it for a small audience,

and we’re competing with each other to capture this audience’s attention.

It’s important to understand this reality from the

start. If you want to sell something, you need to understand exactly what it is

that you’re selling, and exactly who you’re trying to sell it to.

The second thing writers need to realize:

2. You

must decide whether to write what you

want or what they want.

Do you write what you want (an artistic choice) or do

you write what you think will sell (an economic choice)? If you make the

artistic choice, you will be more fulfilled creatively, but you’ll create a product

that may appeal to an even smaller section of the book-reading audience. For

example, horror fiction has a limited appeal, otherwise the bestseller lists

would be filled with horror novels. If you write horror, your audience will be

horror fiction readers, a small group compared to all the readers out there. If

you write a subset of horror – extreme horror, literary horror – your audience

will be even smaller. A few weeks ago on his Facebook page, author and editor

Darrell Schweitzer said that authors of genres with limited appeal should

realize that they are basically selling books to each other, and what’s wrong

with that? I immediately thought of literary fiction, much of it coming out from

small-press publishers with low press runs. Who reads those books? Mostly other

lit-fic authors.

So if you write what you want, there’s an excellent

chance that you’ll have a small audience to sell to, and that no matter what

you do, you won’t be able to enlarge this audience in any meaningful way. My

mother didn’t read much, but when she did, she liked to read romance novels

about nurses. My dad likes to read hard SF and military fiction. Nothing could’ve

gotten them to change their reading tastes, not even having a son who writes in

other genres.

There’s nothing wrong with having a small audience who

appreciates your work, but I think it’s important to recognize this so that your

marketing expectations are realistic. (In other words, you’re not going to get

rich.)

If you’re lucky to love a genre that’s popular, like

Romance (over half the novels published in the USA are Romance), then you can

write what you want and have a much better chance at selling your work because

there’s already a large readership out there.

If you write what they

want, then you need to write in a genre that has a large audience, such as

Romance or Thrillers (or weird porn self-published on Amazon). The pros of this

choice are obvious. Your book will have a stronger built-in appeal for a larger

audience. The cons are that since there are more readers (and thus more money to

chase), you’ll have more competition – and worst of all, you may hate what you’re

writing because you’re writing it for business reasons, not artistic ones.

But whatever choice you make, write for yourself or

write to please an audience . . .

3. Write

the absolute best book you can every time (and never stop trying to write

better).

In other words, create the highest quality product

possible for you to sell. Why would anyone want to buy a poor-quality product

even if they generally like that kind of product? Why would I buy shitty

lemonade when I can buy delicious lemonade? You want to sell something? It

better be damn good. More than that, it better be competitive.

High quality can mean different things for different readers,

of course. Some readers prize literary style and characterization more than

plot, and vice versa. Some prefer fast-paced stories, some more leisurely paced

stories. But while there’s no one-size-fits all definition of high quality when

it comes to fiction, you need to decide what it means to you – and more

importantly, your audience – and strive for that standard.

4. You

need to create an attractive product.

This goes for traditionally published writers as well

as self-published ones – although the self-pubbers obviously have to work a lot

harder at this aspect since they’re going it alone. Intriguing book title, interesting

synopsis, cover art, layout, solid editing, production value . . . Traditional

publishers partner with writers to create an attractive product and then share

in the profits from sales of that product. Self-pubbers need to hire professionals

who can provide these services. Whichever road you choose, at the end of it,

you better have a goddamn good-looking book – outside and inside – if you want to attract readers.

Bottom line: Focus on why you write, how you

write, and to whom you’re writing,

and when it comes time to market your fiction, you’ll be that much ahead of the

game.

Earlier, I mentioned there are lots of resources

available to give you advice on how to market your book after it’s written. Here

are three excellent book marketing resources I recommend:

- Guerilla Marketing for Writers by Jay Conrad Levinson and Rick Frishman.

- No Nonsense, No Gimmick Guide to Marketing Your Book, by Eric Beebe.

- Author’s Guide to Marketing with Teeth, by Michael Knost.

DEPARTMENT OF SHAMELESS SELF-PROMOTION

My novel Eat the

Night will be available from DarkFuse Publications in January. It should be

available for preorder soon.

I’m the featured writer in the latest issue of LampLight magazine. There’s a new

interview with me in it, along with a new story called “Tresspasser.” http://www.amazon.com/LampLight-4-Issue-Tim-Waggoner-ebook/dp/B015YTJV56/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1446933729&sr=8-1&keywords=tim+waggoner&pebp=1446933745367&perid=1R6X6K7YKZD8GNT555QD

The audio version of my surreal zombie

novel The Way of All Flesh is now

available on audio: http://www.amazon.com/The-Way-of-All-Flesh/dp/B0141KWYZ8/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1446933777&sr=8-3&keywords=tim+waggoner&pebp=1446933798718&perid=03ZDK64BTPKQ2JGXPCPE

I have a story in the debut issue of Dreadful Geographic. http://www.amazon.com/Dreadful-Geographic-Issue-Kerry-Prior-ebook/dp/B014QDIWXS/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1446933777&sr=8-2&keywords=tim+waggoner&pebp=1446933994310&perid=03ZDK64BTPKQ2JGXPCPE

My article on writing

with emotional impact, “Once More, With Feeling,” appears in Writers on Writing, Vol. 1. http://www.amazon.com/Writers-Writing-Vol-1-Authors-Guide-ebook/dp/B013NC7Z0Y/ref=sr_1_4?ie=UTF8&qid=1446933777&sr=8-4&keywords=tim+waggoner&pebp=1446934040580&perid=03ZDK64BTPKQ2JGXPCPEFriday, July 31, 2015

Decreasing the Learning Curve

When it comes to teaching fiction

writing, one of the most hotly debated questions is whether the subject can be

taught at all. So much of it is inborn – a feel for language, a sense of

narrative – and just as much, if not more, is developed through an individual’s

reading. The more a person reads, and the more widely he or she reads, the more

that person grows as a writer. And of course you have to write – a lot. So what role can a teacher play,

beyond giving encouragement, pointing out mechanical errors, and passing along

a few tips and tricks? Well, there’s one very important thing that teachers –

and for that matter, editors – can do: we can decrease your learning curve.

Over the course of our careers, we see so many manuscripts from beginners that

we eventually become experts in What Not to Do if you want to get your story

published. (Or, if you’re a self-publisher, What Not to Do if you want your

stories to compete with all the others out there that readers have to choose

from.) So – based on close to thirty years of teaching and writing – here’s my

list of the most common mistakes that beginning writers make.

And as always you can find out more about all my novels and short story collections at my website: www.timwaggoner.com

1. Starting Too Early

I can take a student story, flip to the third

page (sometimes the fourth), place my finger on the paper two-thirds of the way

down, and find what should be the beginning line or situation. I don’t need to

read the story to do this, and I’m right nearly every time. I’m not certain why

beginners do this time and again, but I have some theories. One problem (which

as you’ll see affects other items on my list) is that the vast majority of

stories people experience in their lives are presented in visual media – TV shows,

films, cartoons, etc. These media can immediately set a scene because they can

present a lot of information simultaneously: shape, color, sound, movement. But

prose writers can present information only one word at a time. I think

beginning writers struggle with how to present the same amount of information

visual media do in precisely the same way they do, which is impossible.

Beginners spend paragraphs setting the scene, giving weather reports, detailing

characters’ appearances and fashion choices, info-dumping exposition, and all

the while NOTHING IS HAPPENING. The visual equivalent would be watching a film

where one small bit of visual information appears on the screen, followed by

another bit, and yet another, and so on, as the full picture slowly pieces

itself together. After ten minutes, the picture is fully formed at last, and

only then does the story actually start.

2. The Central Conflict Takes Too Long to

Appear

This problem is similar to the first, and

it can be caused by the same reasons. And sometimes beginners’ stories have an

ill-defined conflict or no conflict at all. In novels, the central conflict

might not appear until several chapters into the book. In general, the central

conflict should appear, even if only in terms of mood or suggestion, in the very

first sentence. This morning, I listened to a short story in audio form about

the interrogation of a man who authorities believe has knowledge about a

devastating new weapon that will be unleashed on the world within days. The man

resists all attempts to get information from him, though, including torture,

without ever speaking a word. A third of the story passed as a bunch of

exposition was presented, and only then did we get to the first interrogation

scene. The story would’ve been far better if it began with the interrogation in

progress and the author then dropped in exposition in bits and pieces as the

story progressed. The central conflict of the story is between the

interrogators and the suspect. That conflict should’ve appeared immediately in

the story instead of being saved for the last third.

3. Only Sight and Hearing are Used

When it comes to description, beginners primarily

use only two of our five senses – sight and hearing. I suspect there are two

reasons for this. One is that these are the two senses we rely on the most,

since they’re the only senses we have that allow us to gather information from

a distance. The other reason is that our media present stories using only

visual and auditory information, and as I stated earlier, we’re all strongly

influenced by these media, much more so than prose. The important thing to

remember about the other senses – smell, taste, and touch – is that because our

body has to be in contact with what we’re sensing for them to operate, they’re

far more intimate senses that sight

and sound. And because of this, they have far more impact on humans. A person

may not appreciate seeing a picture of dog poop, but they’ll have a much

stronger reaction if someone holds it under their nose. Don’t forget to evoke all the senses in your story. You don’t

have to try and cram them into every sentence or even every paragraph; just don’t

neglect them, and don’t forget the power they have.

4. The Point of View Isn’t Immersive

Beginners often write stories the same way

that they watch movies – as if they’re a passive audience member observing from

a distance. They should write with an immersive point of view (whether first

person or third), imagining that they’re inside a single character’s head (at

least for each scene), thinking, feeling, and experiencing the same things the

character is. In this sense, writing fiction is like acting. The writer portrays

the character and then tries to recreate on the page what it’s like to be the

character. This immersive point of view is one of the great strengths written

fiction has over other media. It allows readers to get into someone else’s head

and imagine being that person. Maybe we’ll invent technology one day that

allows the same experience with films and games, but for right now, only

fiction has this capacity. It’s one of the reasons people choose to read

fiction instead of watch it, and you should take advantage of that. In my

fiction writing classes, I’ll put YouTube up on the display screen and show the

class a scene from one of the Bourne movies. We are observers watching Matt

Damon fight bad guys. Then I show them the official music video for Biting Elbows’

“Bad Motherfucker”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rgox84KE7iY

In this video, we view the action from the point of view of a spy, just as if

we are that person. Sure, only sight and sound are evoked in the video, but it

gets the point across about how writers need to imagine the scenes they write,

not as passive viewers but as active participants living them. I always remind

students to consider what thoughts are going through the spy’s head, what

emotions is he feeling, what sort of pain does he experience from injuries

sustained during the battle, how does his body react to all this exertion, etc.

5. No Emotional Core

Stories need to be about more than “This

happened and then this happened.” Unfortunately, beginners – probably because

they’re still learning the basics of constructing scenes – almost never have an

emotional core to their stories. Successful stories need to move readers

emotionally, and they do so by focusing on their characters’ needs, desires,

motivations, and reactions during – and preceding – the events of the story. The

emotional core of Jaws (both the book

and the movie) is Sheriff Brody. He’s sworn to serve and protect the citizens

of Amity, but he faces an enemy hidden in the waters offshore, an enemy he can’t

simply walk up to and arrest. He’s not a native New Englander. He’s come to

town from New York City. He knows nothing about the sea, nothing about boating

and fishing. He’s not prepared in any way shape or form to go after a killer shark.

To make matters worse, his town depends on summer tourist money for its

survival. If he closes the beaches, the town will lose important income, to the

point where the town itself might die. How the hell does Brody protect the

people of his town when, whatever choice he makes, it may well end up hurting

them? The movie may be called Jaws,

but the story isn’t about the shark. It’s about the man who has to deal with the shark. He’s the uncertain knight who

has to face a very real dragon. So think about your characters, about what they

want in your story, about what emotional needs they’re trying to fulfill, and

make sure that this fulfillment (or failure to reach fulfillment) is really

what your story is about.

6. The Story is a Copy of a Copy of a Copy

of Another Story

We spend so much of our lives immersed in

entertainment that the experience beginners draw on to create their fiction is

all too often second, third, or even fourth-hand experience. Instead of using

their own lives and experiences as inspiration for their stories, they write

the same kind of mysteries, romances, science fiction, horror, etc. they’ve read

– or more likely seen on TV or on film. They’re writing stories about other

stories. I tell students that if you’ve ever read or watched a story similar to

yours, don’t write it. Strive to write something original or at least find a

way to put an original spin on it. In Back

to the Future, Marty McFly travels back in time and accidentally prevents

his parents meeting, thereby endangering his own existence. That idea was old

back in the eighties when the film was made. The writers gave the idea a spin

when they focused on teenage Marty developing a relationship with his parents,

learning about what they were like at his age, and learning to accept them for

their faults, and help them meet – for their own sake as much as his. The

writers focused not on the time travel aspect of the story, but on the theme of

family and how that connection can transcend time. (And they also added a

wonderful emotional core to the story by doing this.) Last week, my wife and I

were returning home from attending the Scares That Care convention in Virginia.

We got lost at one point, and we pulled off the highway and into a Pizza Hut

parking lot to check directions. The restaurant was closed, and a man

approached the car. At first I thought he might be an employee checking to see

what we were up to, but it turned out he just wanted to ask for money. My wife

and I left, and that was the end of it. If I wanted to use this as the basis

for a story, I would not make the man a serial killer. Too obvious. I would not

make the man a hungry vampire looking for food. Too cliché. I would not make

him a threat of any sort. That’s exactly what most readers would expect.

Instead, I’d try to come up with something no one would expect. The man is a

friend who’s supposed to living in another country, but who suddenly appears

here. The man is an old boyfriend of the wife who she hasn’t seen in decades.

The man is an older version of the husband who’s somehow appeared in the

present. I could go on, but my point is not only to draw on real experience

(which I did) but then to keep pushing your ideas until they’re no longer run

of the mill but become something interesting, something that only you can write.

7. Expository Lumps

This is one of the most common problems

beginners have. I sure did. Expository lumps are large blocks of explanatory text

provided by the author or delivered through character dialogue. I learned to

avoid these when an editor gave me feedback on a story early in my career,

retyping (back in those pre-Word, pre-email days) an entire paragraph of

exposition from my story to show me what I was doing wrong. “You’ve got a lot

of similar paragraphs in your story,” the editor wrote. I made a fresh printout

of the story, grabbed a red pen, blocked out the paragraph the editor highlighted,

and then went through the manuscript and blocked out at least a half dozen

paragraphs like it. That editor’s comment was one of the most useful pieces of feedback

I’ve ever received, and it improved my writing tremendously. I tell students

who have problems with expository lumps to write their first drafts without any

background information included. Absolutely none. Then I tell them to go back

through the draft and add in only the most minimal amount of background information,

only what is necessary for readers to understand the story, and only add it in

a few sentences at a time, in different places, and in different ways (a bit of

dialogue, a piece of description, short authorial narration, etc.). In longer

work like a novel, you can get away with chunks of exposition because readers

are prepared for a longer reading experience and the chunks seem smaller in

proportion to the rest of the book. But even then you should be as restrained

as possible with exposition.

8. Saving the Best for Last

Beginning writers often save what they believe

is their best idea for the end of the story. This usually means the end is the

only interesting part of the tale. Why would anyone read the rest of it? I tell

students to start with what they think is their best idea and keep writing,

making the story even better as they go. This is also a great way to avoid

writing clichéd stories. An example I always give students is Clive Barker’s

story “The Body Politic.” One of the clichéd story ideas in horror is the

severed hand that has a life of its own and is out for revenge. These stories

end with the hand crawling toward someone, ready to choke them. The idea of the

severed hand is saved for the end. Barker begins his story with the premise

that hands possess lives and desires of their own. All hands. They’re sick of being slaves to us and are waiting for a

messiah to come and lead a revolution against what they call “the tyranny of

the body.” Barker starts with his best idea and develops it from there. In

class, I sometimes have students take the ending of their first story and use

it as the beginning for a brand-new story. It’s a great exercise for teaching

them the power of starting with a great idea/image and continuing on from that

point.

9. Having a Character Die at the End

I can’t tell you how many beginners’

stories I’ve read that end with the main character dying (or worse, narrating

the story in first person even though he or she is dead). Beginners think that

killing a character at the end of their story will have a strong emotional

impact on readers, but it never does. That technique might work in a novel,

where readers have had time to get to know a character, but in a short story? Readers

have so little time to emotionally attach to a character that his or death is

almost meaningless. Besides, death is an easy way out for fictional characters.

If you keep them alive, you can make them suffer more!

10. You Really Want to Write a Script

Students often tell me the reason they

write short fiction is because they really want to write screenplays, and they

figure stories are easier. If you want to write a script, write a script.

Otherwise, write a goddamned story. Both forms are hard as hell to master. Neither

is easier than the other.

Hopefully, some of the advice I’ve given

will decrease your learning curve, at least a little. And if you read all this

and thought, “Well, hell, I already know this stuff,” then feel free to pass

the information along to someone you think might be able to use it. Better yet,

steal the advice and pretend it’s yours the next time you mentor another writer

or teach a class. Because the more we all share what we’ve learned about

writing, the more we all grow, and the better writers we all become.

DEPARTMENT OF SHAMELESS SELF-PROMOTION

The audiobook version of my zombie novel The Way of All Flesh will soon be released

from Audio Realms: http://www.audiorealms.com/cgi-bin/commerce.cgi?preadd=action&key=WAYOFALLFLESH-DL

My novel Dream Stalkers, the sequel to Night

Terrors – about an agent who polices living nightmares with her psychotic

clown partner – is still available: http://www.amazon.com/Dream-Stalkers-Night-Terrors-Shadow/dp/0857663720/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1438368161&sr=8-1&keywords=tim+waggoner

An ebook edition of my first short story

collection All Too Surreal is now available:

http://www.amazon.com/All-Too-Surreal-Tim-Waggoner-ebook/dp/B00UCGXOXM/ref=sr_1_1_twi_2_kin?ie=UTF8&qid=1438368410&sr=8-1&keywords=tim+waggoner+all+too+surreal

My story “Blood and Bone” appears in the shapeshifter

anthology Flesh Like Smoke: http://www.amazon.com/Flesh-Like-Smoke-William-Meikle/dp/0993718043/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1438368538&sr=8-1&keywords=tim+waggoner+flesh+like+smokeAnd as always you can find out more about all my novels and short story collections at my website: www.timwaggoner.com

Wednesday, July 8, 2015

Guest Blog by Jay Wilburn: Do It Yourself Failure

My first short story collection was self-published. It was called Life Among The Zombies and it is a raw little collection of zombie stories that hold up pretty well even just being a roughshod creation. I was still teaching public school when I published that and I started writing and submitting other short stories. I branched out from zombies and started getting some paying publishing credits.

My first novel was picked up by Hazardous Press back when they were a new operation. I had submitted to fourteen publishers and went with Hazardous after a couple others bit at the novel too. My second novel was picked up by Perpetual Motion Machine Publishing. My third is sitting in limbo trying to land an interested party. I guess it is technically not my third since the first book in a twelve book series is out. I wrote another novel or two earlier in my life that were tossed out with my old computer. I suppose I was more picky than I give myself credit for.

There was a point where I was sure I was never going to self-publish again. Publishers, even small ones, will pay for editing, cover art, formatting and will put books up on Amazon for you. These are all things I don’t do well myself.

After I left teaching to write full time, I found that other guys that were making a go at the same thing used self-publishing as one avenue of revenue for their support. I started ghostwriting and freelance writing too to make ends meet as the slower money from my own published fiction came in. Self-published work seemed to fall into that middle range between the faster money of ghostwriting and the longer money of press published fiction.

One thing I learned from other full time self published writers was that the weight of the responsibility rested on the writer. Professional editing and art were the investments that the writer puts into the work. I also added a musical soundtrack to my Dead Song series, so I was hiring a producer and studio musicians to flesh out the radio plays and songs I wrote to make my playing and singing sound like something real that told a story. I invested in all of that and put it out into the world for readers and listeners to accept or reject.

There is a level of control that goes with putting it out yourself along with the responsibility, investment, and risk. If you are going to jump off the cliff, I suppose there is some comfort in knowing you packed your own chute even if you doubt your own skills.

All authors are writing their own ticket in one way or another. Whether one does so in the few moments that are squeezed out to write between life and a day job or in the moments between life and interruptions for a full time writer, we set our own terms in where we submit and what we accept. We all succeed and fail and fail again as often as we choose to get up and try it all again. Self-publishing is just another way to do the game of success and failure. Enough folks are out there doing it that it doesn’t exactly feel like doing it alone. Writing in any form is much like jumping with a parachute you packed yourself, I think.

Check out the latest book and music from a new series by Jay

Wilburn:

The Dead Song Legend Dodecology Book 1: January from Milwaukee to Muscle Shoals –

The Sound May Suffer -

Songs from the Dead Song Legend Book 1: January –

https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/amazing-circle-of-suffering/id996569862?i=996569871&ign-mpt=uo%3D4

Jay Wilburn lives with his wife and two sons in Conway,

South Carolina near the Atlantic coast of the southern United States. He taught

public school for sixteen years before becoming a full time writer. He is the

author of the Dead Song Legend Dodecology and the music of the five song

soundtrack recorded as if by the characters within the world of the novel The Sound

May Suffer. Follow his many dark thoughts on Twitter @AmongTheZombies, his

Facebook author page, and at JayWilburn.com

Saturday, April 11, 2015

Decisions, Decisions . . .

Recently, I had the honor of being

a guest on Don Smith’s radio show at my alma mater, Wright State University.

Afterward, I accompanied Don to a capstone creative writing course he was

taking, and I had the privilege of answering questions from the students and

teachers for an hour or so. Unknown to any of them – at least, I hope it was unknown – I had a splitting

headache and wouldn’t have minded if one of the students had pulled out a 9mm,

pressed the muzzle against my head, pulled the trigger, and put me out of my misery.

I managed to soldier on and hopefully make at least a modicum of sense as I

answered questions, but for all I know, I might have been speaking in tongues.

One of the students asked me how I managed to write so much, so fast. (There are plenty of days when I don’t feel like a fast writer, and days when I don’t write at all – usually because I’m grading papers for a class – but I did my best to answer the question.)

“I’m good at making decisions,” I said.

I went on to explain that, in a sense, you can view writing as nothing more than a series of decisions. This idea, not that idea. This word, not that word. (At least, I’m good at making writing decisions. When I’m looking at the menu at the Cheesecake Factory, that’s a different story.) Later, after my time with the class was over and I’d swallowed some Extra-Strength Tylenol I’d found at the college bookstore, I started thinking. What if a lot of the difficulties people have with writing are actually problems with decision-making?

A couple months earlier, I’d read an interesting article on CNN.com about something called decision fatigue. Stated simply, after an individual makes a number of decisions over time – say during the course of a workday – the quality of those decisions deteriorates. Have you heard the story of how Albert Einstein wore the same kind of clothes every day so he wouldn’t have to expend any mental energy deciding what to wear each morning? Albert understood decision fatigue.

Decision fatigue can affect writers in a number of ways. If you’re writing over a long period of time – say four or five hours – you may find yourself having difficulty getting the words to keep coming. Or maybe you keep writing, but you’re making what, in retrospect, are questionable plot and character choices. Or maybe your brain seizes up and refuses to produce any more text at all.

Most writers have a day job. (I’m a college writing professor.) And if you’ve been making decisions at your job all day – many of which might have been mentally or emotionally taxing – it’s difficult to come home, sit down at your computer, and start making more decisions as you write. So difficult, that maybe you can’t write at all. And the next thing you know, you think you have writer’s block.

So here are some tips to help you head off decision fatigue or deal with it when it rears its ugly head.

Write Before You Need to Make Non-Writing Decisions

This might mean writing before you head off for your day job in the morning or before you decide to work on your home-improvement project or head off to the grocery to stock up on supplies. In my case, it could be all of the above, as well as writing before I sit down to grade papers. The fewer decisions you have to make before you write, the better.

Write in Smaller Chunks of Time and Take Breaks

Instead of writing in marathon sessions lasting several hours, write in one or two hour chunks with thirty minute breaks in between. Studies have shown that even short breaks can help combat decision fatigue. Whatever you do during your break, keep it as decision-free as possible. Don’t shift gears and start working on a different project, don’t answer emails, don’t hop on social media (you’ll end up making decisions about what to post in response to some idiot who’s said something stupid to piss you off.) And take your break away from your writing space, so your mind’s not tempted to keep thinking about your story.

Develop Character and Setting Descriptions Before You Write

If you don’t have a clear notion who your characters are or what settings they live in and move though, you’ll have to make decisions about those aspects when you reach them in your story and fabricate details as you write. But if you write character profiles and setting descriptions, you’ll have details like a character’s eye color, the car he or she drives, and what his or her office at work looks like in hand before you sit down to compose text. You’ll have a wealth of decisions pre-made so you won’t have to waste mental energy as you write scenes.

Outlining Before You Write

Even if you’re normally averse to outlining, consider it as a way of avoiding decision fatigue. You can have a full outline that details every story beat or a more general outline that only gives the story’s basic events. Either approach will help reduce the number of decisions you have to make while actively composing text. I use outlines like this all the time, but I also use smaller, simpler outlines that I create before it’s time to compose a particular scene. That way, I am focused on writing the scene without having to stop and try to figure out what happens next.

To Wrap Up

We need to create a writing space for ourselves, and I’m not just talking about physical space. We need mental and emotional space, and we need time, the most precious and hard-to-come by commodity of all. We need our minds to be at their most creative and productive, and learning how to avoid or at least decrease decision fatigue can go a long way toward making that happen.

And it’s not a bad idea to keep some Tylenol on hand, too. Just in case.

DEPARTMENT OF SHAMELESS SELF-PROMOTION

My latest novel out is Dream Stalkers, the sequel to Night Terrors, is out from Angry Robot Books. Audra Hawthorne and her psychotic clown partner Mr. Jinx are back battling nightmares made flesh, fighting to save both the waking and dream worlds, and trying not to kill each other in the process.

My first short story collection All Too Surreal is now available for the first time as an ebook from Crossroad Press. My other two collections – in case you’re curious – are Broken Shadows and Bone Whispers, and of course they’re still available, too.

My young adult horror novel Dark Art is still out from Past Curfew Press. A young artist’s anger fuels his drawings, bringing them to dangerous life – and none is more deadly than the being called Shrike.

Dream Stalkers: http://www.amazon.com/Dream-Stalkers-Night-Terrors-Shadow/dp/0857663720/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1428789824&sr=1-1&keywords=tim+waggoner

Night Terrors: http://www.amazon.com/Night-Terrors-Shadow-Watch-Book-ebook/dp/B00H12AIT8/ref=sr_1_20?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1428789972&sr=1-20&keywords=tim+waggoner

All Too Surreal: http://www.amazon.com/All-Too-Surreal-Tim-Waggoner-ebook/dp/B00UCGXOXM/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1428789868&sr=1-2&keywords=tim+waggoner

Dark Art: http://www.amazon.com/Dark-Art-Tim-Waggoner/dp/1938644123/ref=sr_1_8?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1428789921&sr=1-8&keywords=tim+waggoner

One of the students asked me how I managed to write so much, so fast. (There are plenty of days when I don’t feel like a fast writer, and days when I don’t write at all – usually because I’m grading papers for a class – but I did my best to answer the question.)

“I’m good at making decisions,” I said.

I went on to explain that, in a sense, you can view writing as nothing more than a series of decisions. This idea, not that idea. This word, not that word. (At least, I’m good at making writing decisions. When I’m looking at the menu at the Cheesecake Factory, that’s a different story.) Later, after my time with the class was over and I’d swallowed some Extra-Strength Tylenol I’d found at the college bookstore, I started thinking. What if a lot of the difficulties people have with writing are actually problems with decision-making?

A couple months earlier, I’d read an interesting article on CNN.com about something called decision fatigue. Stated simply, after an individual makes a number of decisions over time – say during the course of a workday – the quality of those decisions deteriorates. Have you heard the story of how Albert Einstein wore the same kind of clothes every day so he wouldn’t have to expend any mental energy deciding what to wear each morning? Albert understood decision fatigue.

Decision fatigue can affect writers in a number of ways. If you’re writing over a long period of time – say four or five hours – you may find yourself having difficulty getting the words to keep coming. Or maybe you keep writing, but you’re making what, in retrospect, are questionable plot and character choices. Or maybe your brain seizes up and refuses to produce any more text at all.

Most writers have a day job. (I’m a college writing professor.) And if you’ve been making decisions at your job all day – many of which might have been mentally or emotionally taxing – it’s difficult to come home, sit down at your computer, and start making more decisions as you write. So difficult, that maybe you can’t write at all. And the next thing you know, you think you have writer’s block.

So here are some tips to help you head off decision fatigue or deal with it when it rears its ugly head.

Write Before You Need to Make Non-Writing Decisions

This might mean writing before you head off for your day job in the morning or before you decide to work on your home-improvement project or head off to the grocery to stock up on supplies. In my case, it could be all of the above, as well as writing before I sit down to grade papers. The fewer decisions you have to make before you write, the better.

Write in Smaller Chunks of Time and Take Breaks

Instead of writing in marathon sessions lasting several hours, write in one or two hour chunks with thirty minute breaks in between. Studies have shown that even short breaks can help combat decision fatigue. Whatever you do during your break, keep it as decision-free as possible. Don’t shift gears and start working on a different project, don’t answer emails, don’t hop on social media (you’ll end up making decisions about what to post in response to some idiot who’s said something stupid to piss you off.) And take your break away from your writing space, so your mind’s not tempted to keep thinking about your story.

Develop Character and Setting Descriptions Before You Write

If you don’t have a clear notion who your characters are or what settings they live in and move though, you’ll have to make decisions about those aspects when you reach them in your story and fabricate details as you write. But if you write character profiles and setting descriptions, you’ll have details like a character’s eye color, the car he or she drives, and what his or her office at work looks like in hand before you sit down to compose text. You’ll have a wealth of decisions pre-made so you won’t have to waste mental energy as you write scenes.

Outlining Before You Write

Even if you’re normally averse to outlining, consider it as a way of avoiding decision fatigue. You can have a full outline that details every story beat or a more general outline that only gives the story’s basic events. Either approach will help reduce the number of decisions you have to make while actively composing text. I use outlines like this all the time, but I also use smaller, simpler outlines that I create before it’s time to compose a particular scene. That way, I am focused on writing the scene without having to stop and try to figure out what happens next.

To Wrap Up

We need to create a writing space for ourselves, and I’m not just talking about physical space. We need mental and emotional space, and we need time, the most precious and hard-to-come by commodity of all. We need our minds to be at their most creative and productive, and learning how to avoid or at least decrease decision fatigue can go a long way toward making that happen.

And it’s not a bad idea to keep some Tylenol on hand, too. Just in case.

DEPARTMENT OF SHAMELESS SELF-PROMOTION

My latest novel out is Dream Stalkers, the sequel to Night Terrors, is out from Angry Robot Books. Audra Hawthorne and her psychotic clown partner Mr. Jinx are back battling nightmares made flesh, fighting to save both the waking and dream worlds, and trying not to kill each other in the process.

My first short story collection All Too Surreal is now available for the first time as an ebook from Crossroad Press. My other two collections – in case you’re curious – are Broken Shadows and Bone Whispers, and of course they’re still available, too.

My young adult horror novel Dark Art is still out from Past Curfew Press. A young artist’s anger fuels his drawings, bringing them to dangerous life – and none is more deadly than the being called Shrike.

Dream Stalkers: http://www.amazon.com/Dream-Stalkers-Night-Terrors-Shadow/dp/0857663720/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1428789824&sr=1-1&keywords=tim+waggoner

Night Terrors: http://www.amazon.com/Night-Terrors-Shadow-Watch-Book-ebook/dp/B00H12AIT8/ref=sr_1_20?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1428789972&sr=1-20&keywords=tim+waggoner

All Too Surreal: http://www.amazon.com/All-Too-Surreal-Tim-Waggoner-ebook/dp/B00UCGXOXM/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1428789868&sr=1-2&keywords=tim+waggoner

Dark Art: http://www.amazon.com/Dark-Art-Tim-Waggoner/dp/1938644123/ref=sr_1_8?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1428789921&sr=1-8&keywords=tim+waggoner

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)